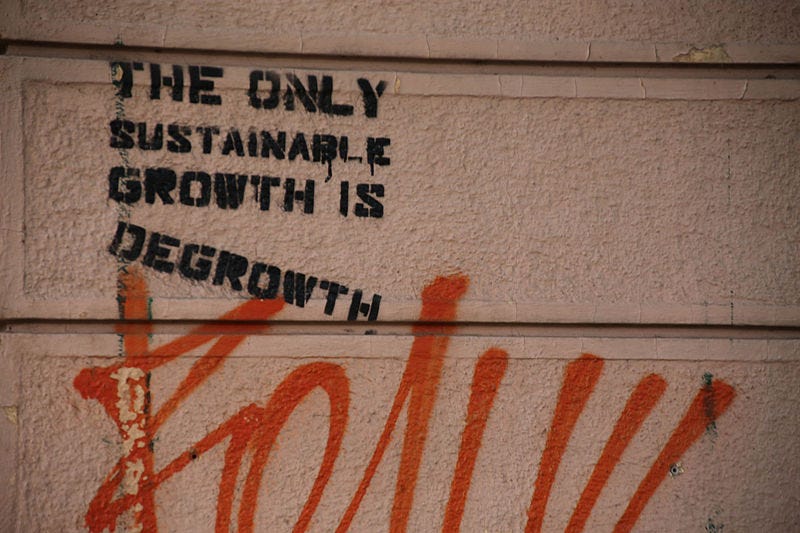

Do we really want degrowth?

Ahead of our Battle satellite discussion in Berlin, writer Sabine Beppler-Spahl examines the consequences of a green agenda in Europe.

While the Battle of Ideas festival in London might be over, our Battle Satellite programme of exciting international and national public discussions continue. We’ve got the launch of the Classical Philosophy Reading Group on Sunday 3 November, via Zoom and Rob Lyons discussing food panics on Tuesday 5 November in Newcastle. There’s a ‘double-header’ of debates in Berlin on Wednesday 6 November on two aspects of civilisation – industrial society and sporting achievement.

On Saturday 9 November we have an afternoon of three debates in Dublin covering misinformation, literary freedom and the impact of EDI. Find out more here. We conclude with a night of free-speech comedy in London at Comedy Unleashed on Tuesday 12 November, Timandra Harkness introducing From social media to AI: a tech moral panic? in Stockholm on Wednesday 13 November and Andrew Calcutt leading a debate on Riots and the role of culturalism on Thursday 14 November in Derby.

Crowds gathered in Berlin last week to protest a new Gender Self-Determination Act. There were solidarity protests outside German embassies all over the world about the law change - which will have a profound impact on sport in the country. Anyone who self-declares as a woman could be eligible to take part in women’s sports. So it’s timely that, at the forthcoming Berlin Battle of Ideas satellite debate, Stephanie Adam, a physiotherapist, former athlete and advocate for women’s rights in sports, will speak about why we should care about sporting achievements.

Ahead of our other discussion in Berlin on industrial society, writer, author and chair of the German liberal think tank Freiblickinstitut e.V., Sabine Beppler-Spahl, explores the popularity of a ‘degrowth’ approach within the EU, and the consequences it is having in Germany today in a guest Substack below.

Sabine will be chairing ‘Has Europe given up on industrial society?’ on Wednesday 6 November, 19:00—20:15, at the Theaterforum Kreuzberg in Berlin. This is the first debate of a two-part event. Tickets are €5, available on the door. Students and apprentices can attend free of charge.

For more information about all of our Satellites, including how to book tickets, hit the button below.

Following the publication of his report on the future competitiveness of the EU, former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi said he had ‘nightmares’ about what could happen to the bloc's economy in the future. Draghi's concern referred to the very real possibility that the EU could fall further behind the US and be overtaken by China. But what is holding Europe back?

Structural problems that need to be solved undoubtedly play a role. But there is another important factor: the rejection of what made Europe's progress and prosperity possible in the first place. For some years now, the central role of economic growth has been downplayed in public debate - especially in academic circles. The connection between prosperity and Western civilisation has been questioned, with the achievements of Western civilisation being increasingly criticised and their downsides highlighted. A deceleration is being called for.

Yet it can hardly be denied that Western civilisation has been both the cause and the consequence of the astonishing success of European economies in recent centuries. Since the Renaissance, this success has been fuelled - to a greater extent than ever before - by freedom of expression and social change. Part of this success has been a series of industrial revolutions that have improved living standards and life expectancy. Freed from the hassle of spending all their energy on earning a living, millions of people were able to live longer, more fulfilling lives. For a long time, this abundance and freedom made Western societies a role model for others.

Scepticism about economic growth and industrial society has gained ground since the late 1960s. Critics point to the unequal distribution of wealth, which leads to injustice. However, it is undeniable that the standard of living for many millions has continued to rise despite these inequalities. Everywhere - especially in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe - people are better off today than they were 20 or 30 years ago. The ‘degrowth ideology’ that is so popular in the Western world is met with understanding by very few here.

In Germany, in particular, the consequences of years of scepticism about growth are now coming to light. The once proud industrial nation is feeling the pressure of international competition. However, it has also made decisions in recent years that have further weakened its competitiveness, particularly in energy policy. Governments seem to have clung to the belief that shrinking our economy is good for both us and the planet.

This misguided notion was not only supported in established circles in Germany - a similar strategy was also pursued in the EU, at least until the Greens' defeat in the last elections in June. As recently as May last year, the EU organised a high-profile conference entitled ‘Beyond Growth’, at which economic growth was presented as a problem.

This attitude is often justified on the grounds of advancing climate change. Those who call for growth are often said to be denying environmental impact. The frustrating thing about this argument is that it exacerbates the problems rather than solving it. If we want to bring climate change under control, we need more growth - not less. Despite the economic downturn, Germany has made surprisingly little progress in reducing its C02 emissions. No wonder, because the deep-seated anti-growth ideology has also fostered fear of nuclear power. Anyone familiar with the eye-watering sums that the energy transition is swallowing up knows that the myth that the sun and wind don't send bills up is simply not true.

An energy-rich world that would create a better standard of living for the entire world population, while reducing C02 emissions, is entirely possible, writes Austrian economist Ralph Schoellhammer in spiked. He focuses on nuclear power, hydrogen, solar, etc. However, he describes degrowth as a ‘suicidal ideology’. Those who rely on alternative energies should demand more economic growth instead of less.

Has Western civilisation lost its appeal? Is degrowth really what we want? What is the relationship between material progress and social progress? Is it ‘civilised’ to want more at the expense of the planet? Or do we need to reassert the importance of humans overcoming the limitations imposed by nature to live longer and more comfortable lives?

These are just some of the questions we’ll be discussing on Wednesday 6 November at our public debate: Has Europe given up on industrial society? Join us at the Theaterforum Kreuzberg for a day of discussion including a second panel - Citius, Altius, Fortius: why should we care about sporting achievements?.

Tickets are €5, available on the door. Students and apprentices can attend free of charge.

Speakers:

Tuna Akarsu, political advisor on finance, Friedrich August von Hayek Society

Cornelis J Schilt, associate professor, History and Philosophy of Knowledge, Vrije Universiteit Brussels; president, Lux Mundi Foundation

Dr Andreas Siemoneit, software architect and system consultant; researcher on growth imperatives

Dr Nikos Sotirakopoulos, visiting fellow, Ayn Rand Institute; instructor, Ayn Rand University; author, Identity Politics and Tribalism: the new culture wars

Chair: Sabine Beppler-Spahl, chair, Freiblickinstitut e.V; CEO, Sprachkunst36; Germany correspondent, spiked

This article was originally published by Ruhrbarone.

Sabine Beppler-Spahl is chair of the German liberal think tank Freiblickinstitut e.V., which organises the Berlin Salons, and she is the Germany correspondent for spiked. She is also a regular commentator for the German – Swiss Kontrafunk radio. She has written for several German magazines and newspapers. She is the author of Brexit: Demokratischer Aufbruch in Großbritannien (Parodos Verlag).

Degrowthers can't even agree on what degrowth even is. The only common element is that the degrowthers, along with other rich elites, won't have to participate in it.