Hung, drawn and cancelled - is this the end of Bonfire Night?

In response to calls to cancel Guy Fawkes celebrations tonight, Niall Crowley delves into the history of our weird and wonderful tradition.

Tonight, the skies will be lit up - not just with excitement about the US election, but with sparklers, fireworks and eco-friendly laser shows for Bonfire Night. But these days, Guy Fawkes gets less of a send-off than he used to - with increasing bans and restrictions on who can celebrate our weird national tradition, and where. In a guest Substack, designer and writer Niall Crowley looks at the history of Bonfire Night, and argues why we should keep it alive - risk and all. This post was originally published on Niall’s Substack: On the Real Side.

Cancel the Guy

Summer is over, the days grow cold and the nights are drawing in. Around the world, ‘tis the season for traditional festivities! Hallowe’en, Diwali and other light festivals, the Mexican Day of the Dead, Harvest Festival and Thanksgiving.

In England, a whole new ‘tradition’ is emerging – the annual cancelling of Bonfire Night. It’s happening across London, from Tower Hamlets in the east to Blackheath, Southwark, Crystal Palace in the south. Up and down the country - from Manchester, Sheffield and Nottingham to Colchester, Pontypridd and Worthing - it’s the same story. Official Bonfire Night events are being snuffed out, in some cases for the fifth year in a row, following Lockdown, of course.

Let’s face it, Guy Fawkes Night or Bonfire Night was just crying out to be cancelled. Too old, too risky, too noisy, too costly, too polluting. Not Net Zero. Too English and inevitably, not too inclusive - too much violent and messy history and tradition.

‘Bonfire Night is a massive pollution event across the UK’, says Leeds University’s School of Earth and Environment. ‘Bonfire Night celebrations contaminate our air with hugely elevated amounts of soot’, argues The Aerosol Society. ‘When fireworks explode, they release very fine dust particles which are rich in toxic metals’, warns the London Air Quality Network. BBC News aren’t keen, nor is the Guardian, Asthma UK, countless campaign groups and nearly every council in England, Scotland and Wales. Even Forge Skip Hire thinks ‘Bonfire Night is having a hugely negative impact on the environment’.

Many of the official events that are taking place are less and less like the traditional Bonfire Night most older Britons grew up with. Local councils are replacing traditional bonfires and fireworks with light and laser displays, and incorporating other autumn events such Diwali. The last Bonfire Night celebration I attended, in Victoria Park in East London, had no bonfire and a pyrotechnic display which celebrated Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

So what happened to Bonfire Night?

We take for granted the big council-organised Bonfire Night events in our towns and cities. However, at least until the early 1980s, Bonfire Night as a national tradition was principally made up of thousands of informal, locally organised events in streets, villages, towns and cities all over the country. It’s no exaggeration to say it was our festival, not something organised for us by the local council. As with so many of our traditional festivals and occasions, once the local authorities became involved, we the public were reduced to passive, often bored observers.

Right up to the late 1970s, it was fairly normal for kids to organise their own bonfire events, usually aided in various ways by parents and other adults. ‘It was a community effort that lasted a month leading up to Halloween’, explains one contributor on a Facebook local history group. ‘I remember the time when a bonfire was in the middle of our council street’, recalls another. If the street was out of bounds for bonfire construction, kids would find a field or a strip of disused land – usually an old Second World War bombsite - at the back of the estate or somewhere on the edge of town.

Once a spot was secured, the preparations would begin. Over a couple of weeks, kids would scour the neighbourhood in search of wood, old furniture or anything that would burn, often knocking on doors and getting adults to chip in with whatever they could find. Bonfires had to be designed, built and guarded in case rival groups found yours and set light to it ahead of the big night. It was serious business.

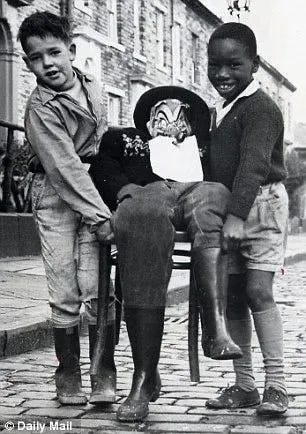

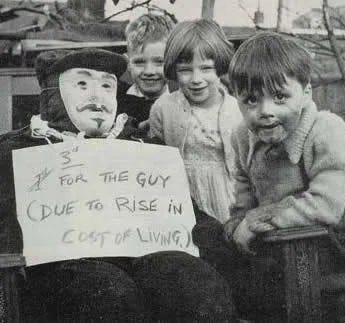

And then there was fundraising, otherwise known as ‘Penny-for-the-guy’. The ‘guy’ was usually made from old clothes, stitched together and stuffed with newspaper, usually with a football and a mask for a head. Once you’d made your super convincing, life-like guy, you’d wheel him up and down the high street. For that, you’d need a home-made cart or borrowed push chair. Outside pubs was always the best pitch for raising large sums of cash - 50p or even £1 in my day. Most savvy kids knew that departing lunchtime pub customers were always the most generous!

The idea was to raise money for fireworks, but even in the 1970s, fireworks were mostly grownups’ responsibility. As I remember, we mostly spent our penny-for-the-guy money on chips and fizzy pop - sparklers if you were lucky! Fathers and uncles would oversee the bonfire and light fireworks, and women would bring or help with food, though often kids made food of their own. ‘We used to throw potatoes in the bonfire to cook! It was great fun trying to get them back out when they were done!’, recalls one Facebook user.

It may seem like pure nostalgia, but it’s important to point out that, for children, it was largely about independent play and self-organisation - for the most part, away from adults. Older children usually took responsibility not only for themselves but for their younger siblings, as in the case of my two older sisters.

In recent years, we’ve come to realise just how important independent play and risk-taking for children is. The late author and child psychologist Helene Guldberg was an early advocate. Drawing on her experiences growing up in Norway, she wrote a ground-breaking book in 2009, titled Reclaiming Childhood: freedom and play in an age of fear:

‘We need to allow children to grow and flourish, to balance sensible guidance with youthful independence. That means letting children play, experiment and mess around without adults hovering over them. It means giving children the opportunity to develop the resilience that characterises a sane and successful adulthood.’

The old traditions of Bonfire Night, stamped out by officialdom, gave kids all of that and more. Obviously, with fireworks and bonfires comes danger, as do many activities. But in the past, we sought to minimise risk and retain a balanced approach to regulating children’s play. In the following years, the balance really shifted away from allowing children to take risks and play unsupervised.

Hung, drawn and quartered?

As for history and tradition - what a crash course in British social and political history for kids Bonfire Night is. The Gunpowder Plot, blowing up parliament, Catholics and Protestants - not to mention poor old Guy Fawkes (or not so poor). Who needs witches and goblins? This is our country’s heritage, and it is gory, sort of fun, but also a great way to begin to understand the chequered history of our unique nation.

Lewes and independence

It's interesting that the most celebrated and high-profile Bonfire Night event now is in the Sussex town of Lewes, where competing local bonfire societies spend months preparing their bonfires, firework displays and, most famously, for the annual procession around town.

According to CNN, Lewes town council actively ‘distances itself from the celebrations and discourages Guy Fawkes Night visitors’. The fact that the council is NOT involved, and its organisation has remained independent, is precisely why Lewes Bonfire has thrived and is now known around the world.

Is it the end of Bonfire Night?

Perhaps the citizens of Lewes have much to teach us, and we need to fight to retain our independence and control over our cultural traditions? When councils cancel and decommission what remains of our traditional festivals such as Bonfire Night, it really is time to take note.

The example of the citizens of Lewes and their fight to retain the independence of their Bonfire festivities is an important one. All over mainland Europe, too, people and communities work to keep alive all kinds of historic festivals and traditions, usually without the aid or oversight of council busybodies. These are not small matters, they are an important component of our everyday lives, part of how we socialise our young, meet our neighbours, and give meaning to our lives. Such precious and ephemeral things cannot be left to councils and ‘professionals’.

Niall Crowley is a designer, writer and former pub landlord living in East London. He studied design history and has a long-term interest in urbanisation, democracy and citizenship. Niall stood as an independent in the 2020 London council elections. He is co-producer and co-editor of the Arts First podcast. Subscribe to his Substack, On the Real Side, here.

That's very kind of you, Johnny. Can we go Penny-for-the-Guying beforehand?

Back in the day fireworks were wonderful (you saved your pocket money and curated your collection with care over weeks. ) But the bonfire was the big deal. And the freedom we were given to do daft and dangerous and essential things was glorious and unimaginable today. https://www.josieholford.com/dark-times/