Ukrainian courage should continue to inspire solidarity, but there is a danger that Zelensky is seen to be begging

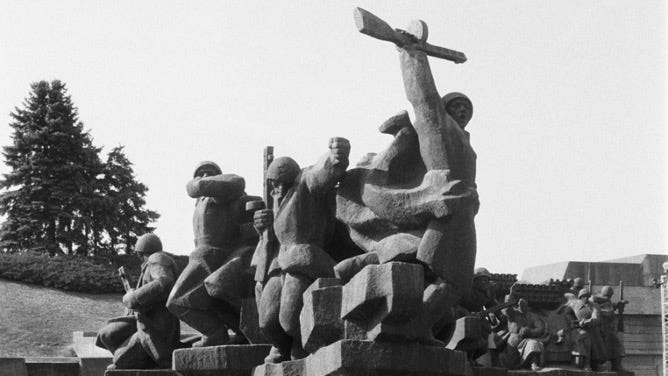

Volodymyr Zelensky has become almost synonymous with the Ukrainian resistance. But also he is a target of increasing cynicism about the West’s support for Ukraine. To begin with, the unexpected change of roles – from satirist to populist to wartime hero – put the man front and centre. Undoubtedly, the early, heroic decisions of Zelensky at the outbreak of war provided the leader with gravitas. This spirit was summed up in his refusal to accept an American offer of evacuation – the phrase ‘I need ammo, not a ride’ being a comment perhaps for the ages. Zelensky seemed able to sum up what so many found so inspiring in Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s supposedly unstoppable invasion: courage.

But has some of this initial inspiration began to wear off?

We should remember that Ukraine’s resistance captured imaginations in a way that seemed to defy easy stereotypes. Of course, there was no lack of virtue signalling in Twitter bios, pro-Ukraine protests with the regular North-London types, and opportunistic photo-ops. But Ukraine’s fight for freedom and sovereignty inspired people much more broadly, with Ukrainian flags next to St George’s crosses in South London high-rises, Ukrainian tridents hastily added to military insignia in squaddie estates on the coast, and Brexiteers organising aid packages. Not to mention the unknown number of volunteer fighters from abroad - made up we can surmise of people from almost all classes and backgrounds.

Boris Johnson, with his unerring instinct for what is popular, made supporting Ukraine the defining legacy of his premiership. The suggestion of some affinity between the Brexiteer desire for popular, national sovereignty and the Ukrainian resistance for the very same thing struck some as fanciful. But people across the UK understood implicitly that Ukraine’s defence was about freedom.

Today, Zelensky continues to fly high in the public imagination. Certainly, at the official level of international politics, he remains the most sought-after photo-op. The embarrassment in the EU when Zelensky decided to visit the UK ahead of the Brussels grandees was so total that a conspiracy of silence was quickly established in case anyone reminded them that they had only themselves to blame. (EU figures, so desperate for some of Zelensky’s reflected glory, had leaked and thus derailed his plans, although no-one knows whether the eventual snub was intentional). Even so, his reception in the UK and Brussels was thunderous.

Despite this, Zelensky has found himself walking an increasingly tough road. The new year has begun with reports of difficulties for the Ukrainian front line – Russia is able to throw men and material at Ukrainian defences in a way Ukraine simply cannot match. While Ukraine won the day on the question of tank deliveries – after the now standard bout of German prevarication and stammering – reports continue to emerge of a new desire in the West to force a negotiation. The Swiss newspaper NZZ reported that CIA director William Burns attempted to broker a deal with Russia in which Ukraine would give up 20 per cent of its territory. At the same time, a spate of editorials and op-eds in the US, following on the heels of a report from the influential RAND corporation, have attempted to make the case for a settlement of the kind Ukraine has repeatedly rejected as unacceptable. (It is perhaps to be expect that, as reports pile up about this new desire for a negotiated settlement, cranks online join increasing numbers of imaginary dots to accuse the West of prolonging the war).

But Zelensky’s problems are not limited to military ones. Below the surface, it is perhaps possible to detect a degree of public weariness towards Zelensky and his repeated calls for new weapons. To take the temperature of certain sections of social media – always a dangerous game but often revealing – Zelensky appears somewhat like a house guest who has overstayed their welcome. At first it was air defence, then it was tanks, now it is planes – what next, some ask? Is this man ever satisfied? Is he ungrateful? Will he demand nuclear weapons?

“The more Zelensky goes cap-in-hand from capital to capital, the less he appears the image of hero and more the image of victim.”

It is difficult to assess how widespread this sentiment is, and how much of it can attributed to recent changes in the algorithm which seem to have boosted anti-Ukraine fakes and disinformation. Some large part of it is also down to the way that even a real war has been swallowed into the culture war: no matter who Zelensky is and what is actually happening in Ukraine, it is often assigned the same side as Davos, Biden and the EU Commission. Being against Zelensky is somehow being against globalism, likewise defending Zelensky has been packaged up with drag-queen story hour.

Nonetheless, with living standards so squeezed, it is almost inevitable to expect some not altogether unfair pushback against the billions heading to Ukraine – a country which no-one needs to be reminded has suffered from corruption and mismanagement. At the same time, seeing national politicians preening over Zelensky is distasteful – shouldn’t they be more concerned with our problems than Ukraine’s? Zelensky is caught in crossfire of attacks on our technocratic and irritating politicians.

But what of the initial solidarity with Ukraine? Has something else changed to sour the mood?

Perhaps we have to return to what made Zelensky – and Ukraine’s cause – initially so popular: courage. We might live in the age of the victim, where everyone from Prince Harry to Shamima Begum seeks the imprimatur of victimhood to claim the moral high ground. But the sense of agency, of heroism, of being a ‘speaker of words and a doer of deeds’, has lost none of its historical appeal. Zelensky, and many millions of Ukrainians, appealed to this aspiration for freedom and agency.

The problem then is this: as necessary as they might be for Ukrainian success, the more Zelensky appeals for weapons, the more difficult it becomes to avoid being cast as the victim. The position of the supplicant has only very rarely been one of great inspiration (we probably have to turn to the Aeneid and Aeneas’ account of his travails to Dido to find a really compelling case). The more Zelensky goes cap-in-hand from capital to capital, the less he appears the image of hero and more the image of victim. In extreme, he risks being seen a beggar rather than a knight.

Zelensky probably knows this. Indeed, his message to the UK parliament seemed almost precisely weighted to challenge this very idea. The words on that helmet – ‘we have freedom, give us wings to protect it’ – were an attempt to articulate the idea that Ukraine is free as it stands, needing only to be adorned with wings; a lion waiting to transform into a griffon. Similarly with the appeal to Churchill, designed to remind us that setbacks might only be temporary: in need this moment, victorious the next, no less courageous throughout.

It is hard to say how successful Zelensky is at keeping the narrative about heroism as opposed to victimhood. One only needs to imagine what all that time hobnobbing with the globalists is doing to him – the globetrotting class, and of course the media, respond far better to victimhood than heroism, and so no doubt encourage it. Critical friends need to keep Zelensky honest here: fewer hugs with journalists, more giving freedom wings.

For now, Zelensky has the unenviable task of seeking the weapons his country needs while still projecting the image of a leader. We, as much as he, need to remember the heroism that solidarity with Ukraine is born from.

Academy of Ideas welcomes debate on this issue. Please leave a comment below or email clairefox@substack.com with any comments. We may feature further discussion in upcoming newsletters. We are planning further public debates on this issue.