Six questions about the British Steel rescue

Parliament may have rushed to pass a law to see off the threat to the steelworks, but without a serious plan, this won’t be the last we hear about it.

Parliament was recalled last Saturday for an emergency session to pass the necessary legislation to prevent British Steel’s Scunthorpe steelworks from closing. But the ramifications go way beyond one steel plant. What is at stake is the future of the UK economy. Here are some thoughts on what this intervention means.

1. Does Scunthorpe show that the government can act, if it wants to?

Whether it makes sense to spend hundreds of millions of pounds on protecting one steelworks is a reasonable question. But in recent years, governments have tended to put their hands up in resignation at the idea of intervention in the economy. (Even if there is lots of regulation of businesses.) The swift action to sustain Scunthorpe raises the question of whether there is a case for broader action to protect and promote industry. The Covid pandemic revealed a country at the mercy of international markets, incapable of providing basic protective equipment to health and social care staff. The Ukraine war caught out many countries that had become over-reliant on cheap Russian energy supplies, with knock-on effects for everyone else. Maybe government needs to think seriously about how we can have an energy and industrial strategy that makes it feasible to produce more of what we need closer to home.

2. Scunthorpe is safe – but for how long?

According to the Chinese owners of British Steel, Jingye, the plant has been losing £700,000 per day. Profitability of the plant has been a long-standing problem. In 2015, Tata, which owned much of the UK’s steel production, failed in its attempts to off-load its European operations. In 2016, the long products part was sold to Greybull Capital for a nominal sum of £1 and renamed British Steel Ltd. By 2019, that company was put into liquidation and eventually sold to Jingye, which invested £330million in capital projects. But even with such investment, the company could not be turned around.

In November 2023, British Steel announced it would close the blast furnaces at Scunthorpe and replace them with two electric arc furnaces. But negotiations on government support for the project stalled late last year and Scunthorpe’s future has been in doubt ever since. In any event, since 1990, the Scunthorpe workforce has declined from 7,300 to 2,700.

The new law passed last Saturday allows the government to direct the operations at Scunthorpe without formally nationalising the plant. But without a serious plan to cut costs and improve markets – steel from Britain faces 25% tariffs to the US in addition to 25% tariffs to export to the EU beyond a tariff-free quota (although see Question 6 below), all in the context of a global glut in steel production – Scunthorpe has been reprieved, not saved.

3. Are Net Zero policies coming home to roost?

One commentator, Ed Conway, has quite reasonably noted the main output of a blast furnace isn’t steel – it’s carbon dioxide. Producing one tonne of steel with a blast furnace produces at least a tonne of carbon dioxide and more likely two or three tonnes. If the UK wants to stop greenhouse gas emissions altogether by 2050, blast furnaces are an obvious target. Even now, UK electricity prices for energy-intensive industries are much higher even compared to Germany or France – never mind China, which produces over half the world’s steel and not in an eco-friendly manner. If the UK wants to keep this kind of heavy industry, those energy prices (along with other green charges) need to be cut sharply, but is the government willing to do so?

4. Do we really need Scunthorpe for national security reasons?

While it is certainly a bit embarrassing that we no longer seem capable of maintaining an industry that can churn out the masses of steel needed to provide the UK’s needs, there certainly seems to be the capacity to produce a wide range of specialist steels for the specific needs of defence. But if the worst were to happen and the UK did become involved in a major war, we would still have plenty of potential suppliers of steel around the world. Indeed, would it make more economic sense to operate a national steel reserve, with supplies bought relatively cheaply from the world market and safely stored, than to try to produce all of our own?

Moreover, even if we do produce our own steel, can we produce the inputs for steel like iron ore and coking coal? Given the government’s mad scramble to obtain such supplies over the past few days to keep Scunthorpe running, the answer is clearly ‘no’.

And looking more broadly, a war effort is not built on steel alone. We need the ability to produce a wide range of things, from food to clothing, to supply the nation at time of war. Particularly significant for modern warfare is the supply of semiconductors – ‘silicon chips’ – to drive computers, drones and all the rest. But these are produced elsewhere, with half the world’s supply coming from Taiwan. Above all, the UK needs reliable and secure supplies of energy – but the government has bet the farm on unreliable renewables instead. So much for ‘national security’.

5. Is the government selective about what jobs it will fight to save?

While much has been made of the devastating impact on the town of Scunthorpe if the steelworks was to close, critics have pointed to seemingly similar cases of Port Talbot in Wales, another steel plant, and Grangemouth in Scotland, which refines oil and produces a range of chemicals. Whether those particular parallels work is another matter, but it seems, for example, that jobs in the North Sea producing oil and gas – a huge source of well-paid work – seem to be of little concern to ministers, with the government banning new production licences. Do jobs really matter to this government when the recent rise in employers’ national insurance will discourage businesses from recruiting staff across the economy?

Perversely, the government seems as interested in creating jobs for middle-class professionals as it is in producing raw materials or manufactured goods. For example, the Welsh Office recently announced £3million for Port Talbot mental health provision. A cynic might suggest it’s unemployed steel workers, but more jobs for therapists…

6. Are tariffs really the problem?

President Trump’s seemingly chaotic application of import tariffs has certainly thrown up serious problems for many exporters. But is America an important market for the kind of steel that Scunthorpe produces? UK Steel notes that the UK exported 180,000 tonnes of steel per year to the US before the tariffs were imposed. But that is out of total UK production of 5.6million tonnes. Moreover, UK exports are more likely to be specialist steel products rather than raw primary steel. Instead, perhaps the failings of British Steel are symptomatic of wider problems in the UK economy, particularly a lack of investment to improve efficiency and lower costs. Rather than fret about Trump’s next move, we need to do more to get our own house in order.

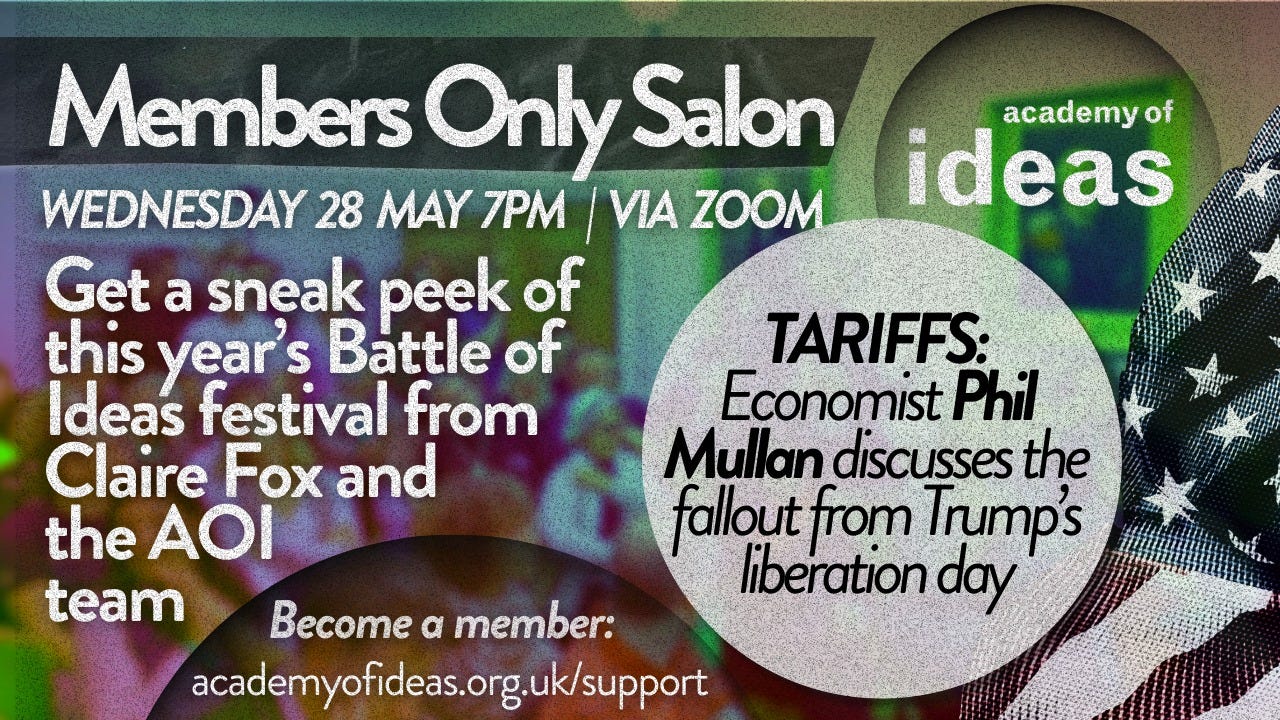

The Academy of Ideas will be discussing the purpose and impact of tariffs at a special online event on Wednesday 28 May for our paid Substack subscribers and Academy of Ideas associates. It will be introduced by economist and author Phil Mullan, and will be a great opportunity to take stock and raise questions and comments. If you would like to take part and are not already a paid subscriber or an AoI associate, sign up as a paid subscriber to this Substack using the button below or become an Academy of Ideas associate here.

I would assert that we do need to maintain an example of a working steelmill as an example of how to do it, a university of steelmaking if you like. Let it go and we'll have a hell of a job resurecting the knowledge and experience without an onshore plant.