Stories from before there was a Scotland

Battle of Ideas speaker Dolan Cummings on why he wrote an historical fantasy novel set in Dark Age Scotland, and how this era can help us think about nationhood, faith and what it means to be human.

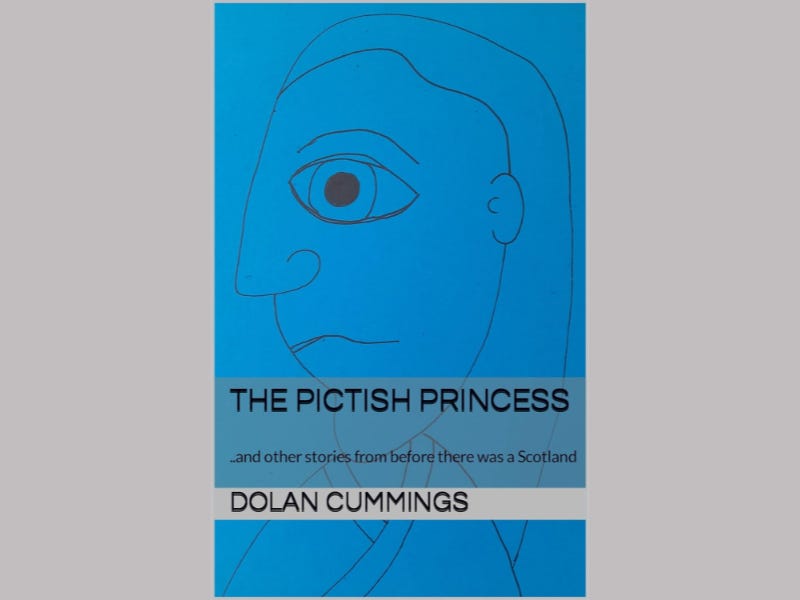

Academic historians tend to disapprove of the term 'Dark Ages', a fact that in my view does not reflect well on their profession. Yes, it's wrong to associate the centuries between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance with nothing but barbarism and ignorance. For some of us, though, the term 'Dark Ages' evokes something else entirely. It stirs something deep within us: a fascination with mystery and a yearning for romance. (‘Early medieval period’ just doesn’t cut it.) It is in this spirit that I began writing The Pictish Princess.. and other stories from before there was a Scotland.

The people described in these interweaving stories speak languages we have lost, forgotten or altered beyond recognition. They live in the shadow of death – from war, want, a simple infected wound or the very act of producing a new life – in a way we find hard to imagine. Their world is dominated by a religion we think we know, but really we do not.

The wider allure of the Dark Ages can be seen in the popularity of books and TV dramas like Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon Stories (televised as The Last Kingdom) and the History channel’s Vikings – not to mention George RR Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (Game of Thrones), Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time (currently on Amazon Prime) and even Andrzej Sapkowski’s Witcher books (Netflix). While these latter examples veer decisively into fantasy, that genre itself owes a lot to JRR Tolkien’s fascination with real early-medieval history.

For me, one of the most appealing things about this period is that so little is known for sure, making it hard to separate fact from fiction. My historical ‘sources’ for The Pictish Princess included myths and saints’ lives as well as reputable history books, which lean heavily on archaeology and are thus necessarily speculative themselves when it comes to describing what life was really like. I call the resulting novel an ‘historical fantasy’ to give myself a little more wiggle room than is normal in historical fiction, not because it’s packed with orcs and dwarves – just the occasional princess, and perhaps a hint of something more sinister.

For the most part, I’ve found the real history is intriguing enough, suggesting a wealth of dramatic possibilities, if not always of a kind we might expect. After all, the Picts are one of the most beguiling nations of ancient Britain, mentioned by Roman chroniclers and surviving as a distinct people into the tenth century. Far from being mere savages, though – with or without the reputed blue tattoos – by the eighth century, when The Pictish Princess is set, they were part of a multi-national Christian civilisation that spanned much of Europe, but had certain distinctive features on the British Isles. In fact, the territory that would become Scotland was shared by four nations roughly corresponding to the four nations of modern Britain – all of which are featured in the novel.

If the Picts, who dominated the north and east of Scotland, were the Scots, then the Gaels of Dalriada in the west (from whom, confusingly, the name Scots comes) were part of a wider Irish culture. In the south west were Britons who spoke a kind of Welsh – the language once spoken throughout most of the island of Britain – while the south east was part of Northumbria, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that would in truncated form become a core part of England.

A thousand years before the Union, let alone the European Union, nationhood was as complicated and vexed a question as it’s ever been. Several of my characters live across and between the nations, fighting in ever-changing combinations, marrying ‘foreigners’ and speaking their languages.

In fact, the five languages of Britain noted by the Venerable Bede were all spoken in what is now Scotland. The fifth was Latin, the language of the Church. And when it comes to historical reality outdoing fantasy, the Christian religion – taken seriously – is surely as mysterious and exotic as any imagined paganism. In a modern society in which Christianity is a taken-for-granted (and often rejected) legacy of the past, it can be hard to imagine what it meant to those who embraced it as ‘good news’ and who lived with the memory of the old gods. For many of my characters, faith is vital and all-pervading. It is not merely pre-scientific cosmology, but a way of thinking about what we call history and politics, as well as ethics and psychology, and of course love and death.

The story begins in the lands of the Britons, where young Morgan is not surprised to find a baby in a basket floating on the river. Then another infant is fatefully separated from its twin and transported as if by magic from Northumbria to Dalriada. And far to the north, an old man tells tall tales to his grandchildren, whose real lives will soon be fantastical enough, not least thanks to an ‘almost princess’ who is almost something else, too. The Pictish Princess shares all their stories.

The Pictish Princess … and other stories from before there was a Scotland by Dolan Cummings is published by Orual Press. It is available in paperback and Kindle formats, or free via Kindle Unlimited.

Scotland will be a major theme of two debates at the Battle of Ideas festival in London on 28 & 29 October. Dolan Cummings is a panellist on ‘Turbocharging devolution: boost or bust for democracy?’. There will also be a discussion on ‘Scotland’s progressive agenda: a warning?’. For more information, visit the Battle of Ideas festival website.

Free subscribers to this Substack get 10% off tickets with promo code SUBSTACK-BOIF23 and paid subscribers get even bigger discounts. See the festival tickets page to find out more.