What UN Women doesn't get about women

Appointing a trans woman as 'women's champion' reveals the superficiality of identity politics.

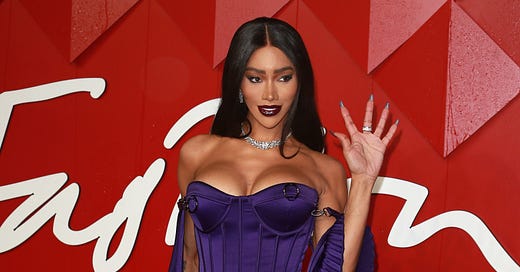

When activist and presenter Munroe Bergdorf was appointed as UN Women’s UK champion last week, many feminists were angry. Bergdorf is a trans woman, and, as a letter to the UN penned by groups like Fair Play For Women, Sex Matters and others put it, ‘unsuitable in every regard’.

The UN appointing someone to represent women who feels like a woman, but isn’t one, isn’t particularly unusual these days. In fact, there has been a bit of a trend for organisations to pick trans women for awards and roles carved out for us ladies for some time. Back in 2015, Glamour magazine caused controversy by announcing Caitlyn Jenner as ‘woman of the year’. Late last year, the influencer Dylan Mulvaney was also awarded ‘woman of the year’ by Attitude magazine, and America’s first lady, Jill Biden, awarded trans woman Alba Rueda with a ‘women of courage’ award - prompting some to quip that it literally takes balls to be a woman of courage.

But if a man being crowned general tsar for women is bad enough, there are also incidents of trans women being appointed in specialist roles for women’s bodily care. Endometriosis South Coast caused a stir after appointing a trans woman as its CEO, arguing that the ‘disease does not discriminate’ (except that men don’t usually get tissue from their womb lining growing elsewhere in their body). Perhaps the most amusing example came from - surprise, surprise - Scotland, where an actual man (no wig or anything) was appointed Period Dignity Regional Lead Officer for Tayside, in charge of talking about periods and menopause to women across the region.

Many feminist organisations have argued that Bergdorf’s appointment to the UN as a women’s champion is an insult to women. As a trans woman, they argue, Bergdorf has little ‘lived experience’ of what it is like to be a woman. It’s easy to understand why many feminists, having fought for women-only spaces, roles, awards and committees as a means to solve the problem of women’s experiences being ignored or drowned out by men, won’t accept being overlooked for a man. But all of this prompts an interesting question: what is it like to be a woman?

Back in 2018, when much of the discussion about the gender wars was only really kicking into gear, we asked this question at the Battle of Ideas festival, with Heather Brunskell-Evans, Chrissie Daz, Kathy Gyngell and Joanna Williams on the panel. At the time, the Labour Party was in a furore over whether trans woman could be included in their all-women shortlists, and the Conservative Party had just announced its plans to reform the Gender Recognition Act. Taking a step back from the outrage on both sides, we wanted to ask whether the idea of womanhood was being pigeon-holed on all fronts, both from those who saw things in a purely biological manner, and those who thought being a woman amounted to frocks and fake boobs.

For me, the appointment of Bergdorf doesn’t show that the UN is at odds with women, or ‘misogynist’ as some have claimed, but rather that such international organisations, NGOs and corporate groups have long been irrelevant to the cause of women’s freedom.

Far from being an important influence on the everyday lives of women, the UN has become nothing more than a platform for celebrities and influencers. The superficiality - and even bias - of UN Women was proven late last year, when it took over two months to respond to the massacre and brutalisation of Israeli women by Hamas. Indeed, it can sometimes be a bit infuriating to be told that all women are represented by an organisation that has some pretty questionable practices. The UN’s ‘Thriving Together’ campaign, focusing on population control, is in part aimed at ‘educating’ women in the developing world to stop having kids to save the planet. Women’s bodily autonomy is only worth discussing if it might stop climate change.

Perhaps we should start asking whether having ‘women’s’ roles is worth it in the first place. The UN could have appointed an inanimate object - it's the massive virtual signal from announcing the appointment that matters, not the job. But there really is no job. If Bergdorf decided to take on the role of women’s champion seriously, and used the platform to campaign for the decriminalisation of abortion, free childcare, an end to the maternity scandal or any of the other issues that really do affect women’s daily lives, I’d be a fan. There’s nothing to say that you have to be a woman to want to tear down the barriers standing in the way of women’s freedom. My dad could do a better job than most self-styled feminist politicians. But the truth is, aside from annoy us with press releases and hashtags on International Women’s Day, UN Women isn’t interested in doing anything substantial for women.

These controversies should serve as a wake-up call to those of us who have been following the trials and tribulations of identity politics for some time. It’s easy to see how the ‘speaking as a woman’ celebration of intersectionality and ‘lived experience’ under previous feminist movements fuelled the mess of identity politics we are in the middle of today. The idea that identity - whether biological or imagined - is what matters in political battles inevitably ends in the absurdity of a trans woman being appointed as women’s champion. Perhaps it’s time we took a step back and asked whether there is a different way to look at the problems women face - not as ‘women’s’ issues, but as challenges of freedom, autonomy and democracy that should concern us all, no matter your pronouns.

From the archive…

Watch and listen to some of our best Battle of Ideas festival debates about feminism and women’s rights.

IN CONVERSATION WITH CAMILLE PAGLIA

Battle of Ideas festival 2016

As one of the most articulate and outspoken polemicists confronting the contemporary feminist focus on policing thought and speech, what does Paglia believe women should be fighting for today? After the gains made by feminism since the 1960s, why are women today so often presented as fragile, helpless victims? What does she make of the political and cultural state of feminism and its near ubiquitous embrace by the establishment? Camille Paglia sits down with Academy of Ideas director Claire Fox to discuss the past, present and future of feminism and to discuss the themes in her forthcoming (and seventh) book, Free Women, Free Men: Sex, Gender, Feminism.

FEMINISM'S CIVIL WAR

Battle of Ideas festival 2021

Does feminism know what it stands for anymore? Are the current divides reflective of a sea-change for feminism, or does the current infighting stem from its roots in identity politics? Can feminism survive its current civil war, or is it time for a new women’s liberation movement?

THE MORALITY OF SURROGACY

Battle of Ideas festival 2023

With a declining birth-rate and growing prevalence of ‘non-traditional’ families, do we need to make all forms of reproductive technology easier to access and come to a moral and legal consensus? How can we balance the bodily autonomy of the surrogate with the interests of the intended parents, all while prioritising what is best for the child? And given the complex moral field in which surrogacy stands, can the process ultimately be justified at all?

BODIES THAT MATTER: TRANSGENDERISM AND TRANSHUMANISM

Battle of Ideas festival 2023

In her recent book, Transgender Body Politics, author and philosopher Heather Brunskell-Evans takes to task the politics of transgenderism. She argues that, for years, Gender Identity Development Theory has become increasingly accepted as a medically ‘progressive’ idea, yet one that bears all the hallmarks of a religion.

GIRL, BOY, OTHER: HOW DO WE TALK TO KIDS ABOUT GENDER?

Battle of Ideas festival 2021

How should we talk to kids about gender – if at all? Is it small-minded to feel uncomfortable about a more open discussion of sex and identity, particularly with younger children at school? Or are we allowing political trends in the adult world interfere with what’s best for kids? Is it a sign of a problem or an expression of greater freedom that, in recent years, there has been a notable increase in young people feeling alienated from their given gender identity? Should children’s gender identity be given the space to be playful, and does the toxic debate in the adult world risk putting limitations on that space for childish exploration?